In the busy heart of Kazir Dewri, Chattogram, there stands a quiet colonial era building that has watched Bangladesh move through empire, partition, war, independence, and political upheaval. Today, people know it as the Zia Memorial Museum (জিয়া স্মৃতি জাদুঘর). But long before it became a museum, it was the Chittagong Circuit House, a government guest house and administrative residence that played many roles at different times. Its walls do not only hold exhibits. They hold memories, debates, and a layered national story.

Where it is and why it matters

The Zia Memorial Museum is located at the Old Circuit House premises in Kazir Dewri, Chattogram, a central area that connects the city’s administrative, commercial, and cultural life. The building itself was completed in 1913 during British rule.

Its importance is not limited to architecture. The building is connected to major national moments, including events around the Liberation War and the assassination of President Ziaur Rahman in 1981. Because of that, the place became both a historical site and a sensitive political symbol. It sits in a space where history, memory, and national identity often meet.

What the building was before the museum

Built as a British era administrative residence (1913)

The Old Circuit House was built in 1913, when British administrative structures in Chattogram were expanding. In colonial South Asia, “circuit houses” served as official residences and rest houses for touring officers and visiting government officials.

The museum’s own history page also describes the building as a British era establishment that later functioned as a government house and then the circuit house during the Pakistan period.

A site touched by 1971 memories

Chattogram played a decisive role in 1971, and the Circuit House appears repeatedly in accounts of those days. One well known recollection published by The Daily Star describes the Bangladesh flag being hoisted on the Circuit House on 17 December 1971, shortly after the Pakistani surrender.

(There are different public narrations of exactly how every event unfolded during those days, but what remains consistent is that the Circuit House became a symbolic place in the early hours of Bangladesh’s independence in Chattogram.)

Before 1993, it remained a Circuit House

Even after independence, the building continued to be known as the Circuit House, serving administrative functions. Over time, it accumulated layered identity: colonial architecture, wartime memory, and later political history.

How it became the Zia Memorial Museum

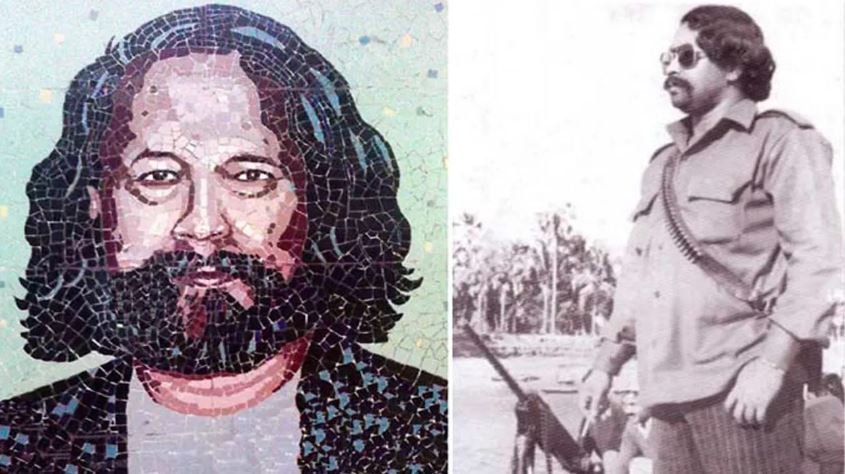

The turning point: May 30, 1981

On 30 May 1981, President Ziaur Rahman was assassinated in this building during an uprising by a group of army officers.

From that moment, the building’s identity changed forever. It was no longer just a colonial era government house. It became a site of national tragedy and political history.

Cabinet decision and the long path to a museum

According to the museum’s official site, a cabinet meeting on 3 June 1981 decided that the Chittagong Circuit House, where Zia was assassinated, would be turned into a memorial museum.

However, the museum did not open immediately. The same official history notes that the project was included in the annual development program for 1992–1993, following a decision at a “Nikar” meeting on 9 August 1992.

Then came the formal handover and renovation steps:

- The Chattogram district administration handed over the old Circuit House to the Bangladesh National Museum on 9 January 1993.

- The Bangladesh National Museum then handed it to the Public Works Department (PWD) for renovation and development work.

Finally, the museum was inaugurated in 1993.

So, in a simple timeline:

- 1913: Building completed as Circuit House during British rule

- 1981: Assassination of President Ziaur Rahman in the building

- 1981 (June): Cabinet decision to convert it into a museum

- 1992-93: Development and renovation phase

- 1993: Museum inaugurated

What makes the museum special

The Zia Memorial Museum is not just a building with framed photographs. Its specialty is that it tries to present a complete narrative experience around:

- a historic building,

- a national political figure, and

- major national events connected to Chattogram.

17 galleries and a “site preserved” approach

A widely cited description of the museum is that it presents Ziaur Rahman’s life across 17 galleries, and preserves the assassination site within the building as part of the exhibition experience.

This matters because many museums display objects, but fewer preserve a specific “room of history” as a central part of the visitor experience.

Rare objects and historic artifacts

The museum is also known for preserving historically significant items, including personal belongings and objects linked to major national moments. One prominent mention is that the museum preserves a microphone associated with the proclamation broadcasts from the Kalurghat radio center era, presented in connection with the independence narrative.

The museum’s official site provides more detail on collections and growth over time, stating that Bangladesh National Museum authorities initially collected 743 antiquities, and that the total collection later increased to 902.

Even if a visitor is not politically engaged, the collection itself can be a learning point for students and researchers because it combines personal items, documents, photographs, and curated historical materials under one roof.

A branch under national museum administration

The museum is described as being run under the Bangladesh National Museum framework and connected to the Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

This makes it part of a wider national heritage system rather than a private or informal memorial space.

A place of history and also controversy

In Bangladesh, memorial sites linked to political leaders often sit inside public debate. The Zia Memorial Museum has also faced political controversy. For example, in 2021, Dhaka Tribune reported comments from a state minister suggesting that the museum name or presence in the Circuit House would be removed, arguing from a Liberation War heritage perspective.

Whether people agree or disagree with such positions, this shows one reality: the building is not only a museum. It is a national symbol that different political narratives try to claim. That is another reason its preservation and management become especially important. A historic building should be protected even when politics changes, because physical heritage is harder to replace than opinions.

Visitor experience and educational value

When the museum is accessible, its value is strongest for:

- Students learning about Bangladesh’s modern history through real objects and curated galleries

- Researchers who want physical context, archival displays, and heritage architecture

- Visitors to Chattogram who want to understand why this city is central to national history

Museums are also social classrooms. They teach without forcing a single lecture style. People walk at their own pace. They pause at what matters to them. That is why a museum like this can remain important for future generations, regardless of shifting political views.

Current situation: vulnerability, closure concerns, and the mayor’s call

The museum building is in a vulnerable condition and has suffered damage, with concerns about maintenance and preservation. You also shared that the Chattogram City Corporation mayor, Dr Shahadat Hossain, visited the museum after earthquake related damage and called for repair, renovation, and preservation so it can be protected for future generations.

During the visit, the museum’s administrative and security official reportedly highlighted existing problems to the mayor, and the mayor emphasized that the building is historically significant and should not be left to decay. (Your provided report frames this as an urgent heritage preservation issue, not just a political issue.) A related video report of the mayor’s visit has also circulated online.

A museum is not preserved by memory alone. Old buildings need structural care, safety upgrades, and consistent funding. Once a heritage building begins to weaken, delays make repair more expensive and sometimes impossible. If the museum remains closed or partially inaccessible, the public loses an educational space, and the city loses a historic landmark that could otherwise strengthen cultural tourism and civic pride.

The mayor’s message, as reflected in the reports you shared, can be used as a strong closing argument in your featured story: Chattogram has many modern developments, but protecting key historic sites like the Old Circuit House is also a form of development. It keeps the city connected to its past while educating the next generation.

Closing thought: why this museum still deserves attention

The Zia Memorial Museum stands at an unusual intersection. It is a colonial era building from 1913. It carries Liberation War era memories connected to the Circuit House. It is a site of national political tragedy from 1981. And it became a formal museum through a long administrative process that ended with its 1993 inauguration and national museum management.

That combination makes it more than a single story. It is a layered heritage site. If it is repaired, preserved, and reopened with proper care, it can continue to serve as a space for learning, reflection, and civic conversation, especially for young people who only know these events from textbooks.