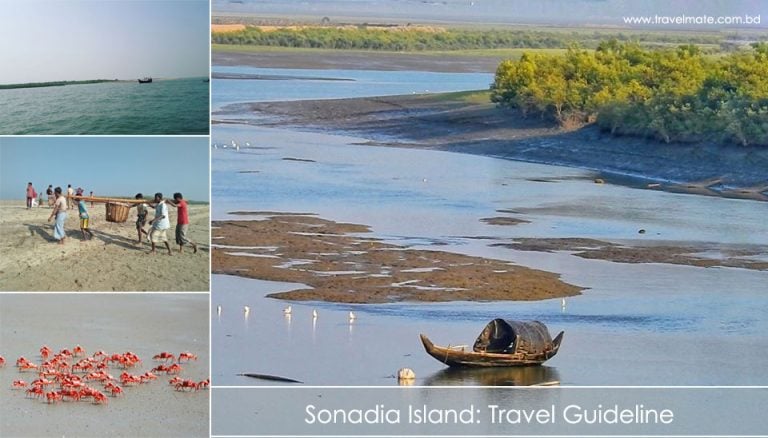

A Silent Island with a Powerful Secret

Off the coast of Maheshkhali in Cox’s Bazar lies Sonadia Island, a serene nine-square-kilometer patch of green surrounded by the turquoise waters of the Bay of Bengal. The world has long known this island for its mangrove forests and migratory birds, but recent findings have transformed its image completely. According to a study published in the journal Discover Geoscience, the Sonadia Island mineral discovery has revealed more than 700,000 tons of heavy minerals hidden beneath its sands.

This discovery came through a joint effort by researchers from Otago University in New Zealand, Western University in Australia, and Jahangirnagar University in Bangladesh. Their study suggests that Sonadia’s mineral-rich sands could hold the potential to reshape Bangladesh’s future in mineral extraction and industrial development.

The researchers identified several valuable minerals, including garnet, ilmenite, magnetite, zircon, rutile, and monazite. Each of these elements is used globally in industries like aerospace, electronics, and renewable energy. To understand why this is important, one only has to look at how similar mineral sands transformed economies in countries like Australia and India, both of which are now major players in global titanium and rare earth markets.

What the Sonadia Island Mineral Discovery Reveals

The findings are striking. The sand composition analysis shows that garnet makes up 51.52%, while ilmenite constitutes 38.14% of Sonadia’s heavy mineral content. Smaller percentages belong to magnetite, zircon, rutile, and monazite. According to researchers, garnet alone accounts for nearly 276,000 tons, while ilmenite adds another 215,000 tons to the total mineral estimate.

Garnet is a mineral prized for its strength and durability. It is used in waterjet cutting, sandblasting, and industrial polishing, as explained by Geology Science. Ilmenite, on the other hand, is the main source of titanium dioxide, which powers industries from paint production to aircraft manufacturing, according to USGS.

These numbers have sparked optimism but also caution among experts in Bangladesh’s mining community.

Weighing Potential Against Practicality

Dr. Mohammad Aminur Rahman from the Institute of Mining, Mineralogy and Metallurgy (IMMM) in Jessore warns against premature excitement. “Seven lakh tons sounds promising,” he notes in an interview with The Daily Star. “But we must assess whether it is economically viable to extract.”

The extraction and refinement of heavy minerals are expensive processes. Bangladesh’s experience in large-scale mineral operations is limited, and infrastructure on Sonadia Island remains minimal. Earlier geological surveys in the 1980s estimated over 21 million tons of heavy minerals across the wider Cox’s Bazar-Teknaf-Maheshkhali belt. However, many of those deposits remain untouched due to technical and environmental challenges.

As Mining Technology notes, mining in coastal zones often requires advanced dredging systems, strict waste control, and coastal protection mechanisms. Without proper safeguards, extraction could accelerate erosion or destroy marine habitats.

The Environmental Crossroads

Sonadia is not just a potential mining site; it is also an ecologically sensitive zone. The island shelters migratory birds, marine turtles, and endangered mangroves. Conservationists argue that mineral extraction could threaten this fragile ecosystem.

In 2017, the Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA) received approval to develop an eco-tourism park on 9,467 acres of Sonadia land. But in 2024, the High Court halted that move after the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA) filed a petition. As reported by Dhaka Tribune, the court ordered that the land be handed back to the Forest Department to protect biodiversity.

This legal tug-of-war highlights the nation’s struggle between conservation and development. Should Bangladesh exploit Sonadia’s mineral wealth, or should it preserve the island as a sanctuary for wildlife and sustainable tourism? Experts believe that striking a balance will define Bangladesh’s long-term coastal policy.

Global Context and Strategic Importance

Worldwide demand for heavy minerals has grown dramatically. The titanium dioxide market alone is now valued at $20 billion annually, according to Grand View Research. Rare earth minerals like zircon and monazite are critical in solar panels, electric vehicles, and defense systems.

As the world moves toward renewable energy and advanced technology manufacturing, countries with such resources gain geopolitical leverage. For instance, China currently controls over 60% of global rare earth supply chains. Bangladesh, if it acts wisely, could enter this market with careful planning, transparent regulations, and strategic partnerships.

However, experts warn that inviting foreign corporations too early might limit national benefits. Dr. Mohammad Badrudozza Miah, Chair of Dhaka University’s Geology Department, told The Business Standard that Bangladesh should first strengthen local geological capacity before opening doors to international firms. “Rare earth elements are a national asset. Let’s build our own processing capabilities first,” he emphasized.

The Economic Promise for Bangladesh

If managed properly, the Sonadia Island mineral discovery could diversify Bangladesh’s economy beyond textiles and remittances. According to projections from the Ministry of Power, Energy, and Mineral Resources, processing just 10% of the annual sediment from major rivers like Jamuna and Brahmaputra could generate nearly ৳2,000 crore in annual revenue.

This aligns with national ambitions under Vision 2041, which aims to transform Bangladesh into a high-income nation through sustainable industrial growth. Harnessing mineral sands could support industries like ceramics, glass manufacturing, electronics, and defense, all of which rely heavily on imported raw materials today.

But economic gains will depend on environmental management and technological efficiency. Countries like Kenya and Mozambique have faced public backlash due to poor oversight of coastal mining operations. To avoid repeating their mistakes, Bangladesh must ensure transparent licensing, community engagement, and continuous ecological monitoring.

Protecting Nature While Pursuing Growth

Environmentalists suggest that Sonadia Island can serve as a model for responsible resource governance. If the government adopts sustainable extraction policies and modern rehabilitation methods, it can ensure minimal ecological damage. For example, UNEP advocates for reforestation, wetland restoration, and sand recycling practices to offset the impact of coastal mining.

Sonadia could also integrate eco-tourism alongside mineral development. The region’s scenic mangroves, coral patches, and migratory birds offer immense tourism potential. Responsible management could turn the island into both a mineral and eco-tourism hub, similar to how Western Australia balances mining with nature-based travel.

Policy, Planning, and the Path Ahead

The Department of Geological Survey of Bangladesh (GSB) has confirmed plans for further exploration in the coastal belts of Cox’s Bazar and Maheshkhali. Authorities are also expanding research into river sediments, which contain similar mineral compositions. Experts believe that these inland sources may prove easier and more sustainable to mine than fragile coastal zones.

Developing a modern mineral economy will require collaboration between universities, government agencies, and the private sector. Training geologists, upgrading laboratories, and adopting AI-based exploration technologies will be essential steps. Several researchers are already working on AI mapping projects with support from the Asian Development Bank.

Public awareness will also be critical. Without community support, even the best resource policies can face local resistance. Transparent communication, fair compensation, and ecological guarantees will be necessary to earn public trust.

The Future Beneath the Sands

Sonadia Island today stands at a fascinating crossroads. It is a tiny landmass with enormous potential scientific, economic, and ecological. Beneath its calm surface lies a wealth that could help Bangladesh enter the global mineral market, if managed with wisdom and care.

The Sonadia Island mineral discovery is more than a scientific revelation. It is a test of Bangladesh’s ability to balance ambition with responsibility. The island’s quiet sands whisper of opportunity, but also of caution. In the years ahead, Sonadia could become a case study in how nations navigate the thin line between prosperity and preservation.