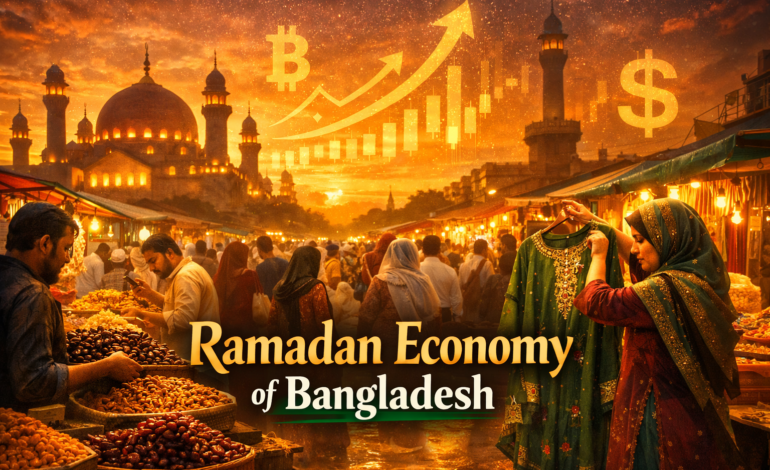

How Ramadan impacts Economy of Bangladesh?

Ramadan plays a uniquely powerful role in the economy of Bangladesh, shaping consumption, trade flows, financial transactions, and industrial activity every year. During this month, household spending rises sharply, import volumes increase, retail sectors expand, and charity flows intensify. Economists often describe Ramadan as a short but intense seasonal stimulus that temporarily accelerates economic circulation across multiple sectors.

The impact begins even before the month starts. Traders, importers, and wholesalers begin stocking essential commodities months in advance, while banks and regulators adjust policies to facilitate imports and ensure liquidity. This pre-Ramadan cycle creates a surge in demand, increases trade financing, and stimulates logistics and supply chain activities.

In Bangladesh, where nearly 90 percent of the population is Muslim, Ramadan affects the economy more strongly than most religious events elsewhere in the world. Consumer behaviour changes significantly, with spending patterns shifting from regular consumption to food, clothing, charity, and religious activities.

This seasonal shift influences everything from agricultural imports to textile sales, retail profits, financial transactions, remittance utilisation, and government policy responses.

Import surge before Ramadan, a mixed impact on the economy

One of the most visible impacts of Ramadan on the economy is the surge in imports of essential commodities. Bangladesh relies heavily on imports for key Ramadan food items, including chickpeas, dates, lentils, edible oil, sugar, and onions.

To stabilise markets, the central bank regularly relaxes import regulations ahead of Ramadan. Authorities have allowed delayed payments and reduced margins for importing essential goods such as rice, wheat, pulses, edible oil, sugar, chickpeas, and dates, ensuring smoother supply and price stability.

Data show significant increases in import volumes during the Ramadan preparation period. Imports of lentils rose by about 32 percent year-on-year to 251,000 tonnes in FY2024-25, while chickpea imports surged by 188 percent to nearly 49,000 tonnes.

Demand estimates also highlight the scale of consumption during Ramadan. Soybean oil demand reaches roughly 300,000 tonnes, sugar demand about 300,000 tonnes, chickpea demand between 150,000 and 200,000 tonnes, and date consumption around 60,000 to 80,000 tonnes.

Food consumption patterns and price dynamics

Ramadan alters consumption behaviour dramatically, particularly in food markets. Families consume more protein-rich and processed foods, including fried snacks, pulses, fruits, and sweet items. This surge in demand often leads to price volatility.

Despite increased imports, price spikes frequently occur due to supply chain inefficiencies and market practices. For example, retail prices of dates increased by Tk 50 to Tk 100 per kilogram within a short period during the Ramadan preparation phase.

In addition, the sudden demand growth can trigger speculative trading and stockpiling, which sometimes leads to artificial shortages. This phenomenon creates inflationary pressure in the food sector, reducing real purchasing power among low-income households.

However, increased imports and regulatory monitoring sometimes help stabilise prices, showing how policy interventions play a crucial role in managing Ramadan-related economic fluctuations.

Clothing and Eid shopping, a massive retail economy

Another major Ramadan-driven force in the economy is the clothing and retail sector, especially due to Eid-ul-Fitr shopping. This period generates one of the largest seasonal retail booms in Bangladesh.

Retail estimates indicate that traders expect around Tk 2.5 lakh crore in sales during the Eid shopping season, with about 80 percent of consumer budgets spent on clothing alone. Shopping activity intensifies in the last two weeks of Ramadan, benefiting garment manufacturers, textile suppliers, transport providers, shopping malls, and informal street vendors.

This retail surge supports employment across the value chain, from factory workers to sales staff and delivery services. It also stimulates domestic industries such as footwear, cosmetics, jewellery, and electronics.

As a result, Ramadan acts as a major consumption-led growth driver in the national economy.

Financial transactions and money circulation

Ramadan significantly increases the circulation of money throughout the economy. Several financial factors contribute to this phenomenon.

First, remittances often rise before Eid as migrant workers send extra funds to support family spending. Second, banks experience increased transaction volumes due to business imports, retail payments, and charity transfers.

Third, large volumes of zakat and donations are distributed during Ramadan, creating informal redistribution of wealth that supports low-income households and stimulates local markets.

The cumulative effect is increased liquidity in both formal and informal sectors, which strengthens short-term economic activity.

Charity economy and social redistribution

The charity ecosystem during Ramadan represents a unique component of Bangladesh’s economy. Zakat, fitra, and voluntary donations channel billions of taka annually into social welfare.

These funds are used for food distribution, clothing purchases, education support, and healthcare assistance for the poor. As a result, Ramadan contributes to temporary reductions in inequality by increasing consumption capacity among low-income groups.

This redistribution effect also supports small businesses, local vendors, and informal workers.

Logistics, transport, and employment effects

Ramadan significantly boosts logistics and transportation activities across the economy. Import shipments increase, wholesale distribution expands, and retail supply chains operate at full capacity.

Transport demand rises sharply due to shopping travel, labour migration, and Eid homebound journeys. Temporary employment opportunities also increase in retail, food services, and logistics sectors.

Thus, Ramadan acts as a seasonal employment generator, particularly benefiting informal workers.

Inflation and inequality risks

Despite its positive impacts, Ramadan also creates challenges for the economy. Price inflation remains a major concern, particularly for essential food items. Low-income households often struggle to afford increased costs of staple foods, leading to reduced nutritional intake or increased borrowing.

Additionally, higher import demand can widen trade deficits and strain foreign exchange reserves. Supply chain disruptions and speculative trading can further worsen price volatility. These challenges highlight the need for stronger regulatory oversight and market monitoring during Ramadan.

Government policy interventions and economic management

To manage Ramadan-related economic fluctuations, policymakers take several steps each year. These include easing import rules, monitoring markets, increasing public food distribution, and coordinating with traders.

For example, the central bank’s decision to allow delayed payments for essential imports helps ensure adequate supply and stabilises prices during Ramadan.

Government agencies also conduct market inspections and distribute subsidised goods to reduce inflationary pressures. Such interventions demonstrate how Ramadan requires active macroeconomic management.

Ramadan as a seasonal economic cycle

Overall, Ramadan represents a powerful seasonal cycle within the economy of Bangladesh. It simultaneously stimulates consumption, boosts trade, increases employment, and redistributes income through charity.

At the same time, it introduces challenges such as inflation risks, import dependency, and trade imbalances. The net impact remains largely positive, as Ramadan acts as a short-term economic stimulus that energises multiple sectors, from agriculture and imports to retail and services.

Ramadan and the broader economic landscape

Ramadan plays a transformative role in the economy of Bangladesh each year. It increases imports, accelerates retail sales, boosts financial transactions, and strengthens social redistribution mechanisms.

The month generates billions of taka in additional economic activity, particularly through food trade and Eid shopping. Yet it also creates policy challenges related to price stability, trade deficits, and market regulation.

Ultimately, Ramadan represents both a cultural and economic phenomenon, reflecting how religious practices can shape consumption patterns, trade flows, and social welfare within a developing economy.

Its overall contribution underscores the deep interconnection between faith, society, and economic life in Bangladesh.