Intercultural Exchange in Border Regions of Bangladesh

Borders are often imagined as lines of separation, political boundaries drawn to divide nations, languages, and identities. In Bangladesh, however, border regions tell a more complex story. Along the edges of the country, culture does not stop at checkpoints. Instead, it flows quietly through markets, dialects, food habits, festivals, and everyday interactions. These borderlands function as living zones of intercultural exchange, shaped by history, migration, trade, and shared ecology.

From the northern edges of Rangpur to the hills of Bandarban and the coastal belt near Myanmar, border communities in Bangladesh live in constant cultural conversation with neighboring regions. Their lives reveal how borders divide states but rarely divide culture.

Language Without Borders

One of the most visible markers of intercultural exchange in border regions is language. In many border districts, Bangla is spoken with accents, vocabulary, and sentence patterns influenced by neighboring countries. In northern Bangladesh, particularly in areas near West Bengal and Assam, local Bangla blends seamlessly with regional dialects that sound familiar on both sides of the border. Words, idioms, and pronunciations travel freely, even when people do not.

In the Chittagong Hill Tracts and parts of Cox’s Bazar, everyday speech often shifts between Bangla, indigenous languages, and Rohingya or Arakanese dialects. People switch languages based on context, at home, in the market, or with visitors, creating a fluid linguistic environment. This multilingualism is not taught formally; it is learned naturally through proximity and daily interaction.

Markets as Cultural Meeting Points

Border markets, particularly weekly haats, play a central role in intercultural exchange. These spaces are more than economic hubs; they are social and cultural intersections. In districts near India and Myanmar, traders, farmers, and shoppers bring with them not only goods but also habits, gestures, and stories.

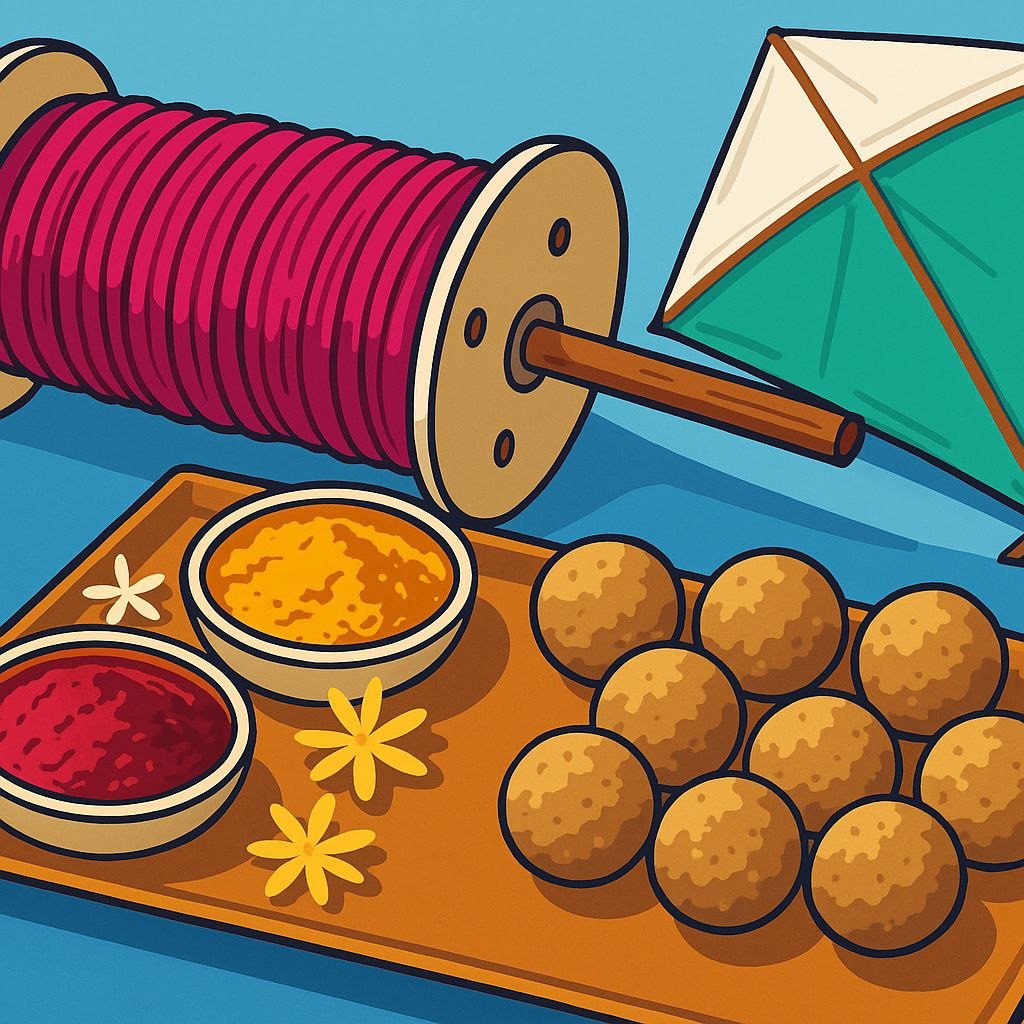

Spices, textiles, dried fish, betel nuts, and handmade tools circulate across these markets, reflecting shared culinary and occupational traditions. Food tastes in border areas often resemble those across the border more than those in distant parts of Bangladesh. Cooking styles, preservation methods, and seasonal food choices reveal a long history of shared living that predates modern borders.

Shared Rituals and Spiritual Spaces

Religious and spiritual practices in border regions often reflect a deep history of coexistence. Shrines, mazars, temples, and sacred natural sites are sometimes visited by people from different faiths and cultural backgrounds. These shared spiritual spaces create forms of intercultural belonging that do not fit neatly into formal religious categories.

In some border communities, festivals are observed with blended rituals, where local customs merge with practices from neighboring regions. The rhythm of celebration is shaped as much by seasonal cycles and agricultural life as by religious calendars, reinforcing a sense of shared cultural ground.

Food as Cultural Memory

Food in border regions carries memory. Recipes are passed down through generations, often unchanged by national identity. Dishes made with fermented ingredients, dried fish, bamboo shoots, or wild greens reflect ecological similarities across borders. These foods tell stories of survival, adaptation, and shared knowledge.

In areas bordering Myanmar and India’s Northeast, cooking methods and flavors differ noticeably from mainstream Bangladeshi cuisine. Yet, within these communities, such food feels entirely normal, part of everyday life rather than a marker of difference. Food becomes a quiet archive of intercultural history.

Everyday Life in the Borderlands

Intercultural exchange in border regions is not always dramatic or celebratory. It exists in ordinary routines: how people greet each other, how elders are addressed, how disputes are resolved, and how hospitality is offered. Clothing styles may reflect neighboring influences, adapted to local climate and resources. Music, storytelling, and folk practices often echo across borders, carried by memory rather than movement.

At the same time, border communities also experience tension, surveillance, and uncertainty. Political borders bring restrictions that complicate long-standing cultural connections. Yet, even under these pressures, everyday intercultural life continues in subtle ways, often unnoticed by those far from the borders.

Culture Beyond the Line

Intercultural exchange in Bangladesh’s border regions reminds us that culture is not confined by political geography. These regions show how people live with layered identities, shaped by proximity, history, and shared environments rather than official narratives.

To understand Bangladesh fully, one must look not only at its center but also at its edges. In the borderlands, culture is not fixed; it is negotiated daily, spoken in mixed dialects, cooked into meals, practiced in rituals, and carried quietly across invisible lines. Borders may define nations, but in everyday life, culture continues to move freely, reshaping itself with each interaction.