History of the Armenians: The Merchant Community That Shaped Old Dhaka

History of the Armenians: The Merchant Community That Shaped Old Dhaka

For more than three centuries, a small but remarkably influential Armenian community played a defining role in the economic, social, and cultural evolution of Dhaka. Though no Armenians permanently reside in the city today, their legacy survives in place names, institutions, architecture, and in one of Old Dhaka’s most iconic landmarks, known as the Armenian Church of the Holy Resurrection.

The story of the Armenians of Dhaka is not merely a footnote in colonial history; it is a testament to how global trade networks, minority enterprise, and cultural exchange shaped Bengal’s urban life long before modern globalization.

Arrival and Early Trade: 17th–18th Century

Armenians first arrived in Bengal in the early 17th century, during the Mughal era, primarily as merchants. Many had migrated from the Safavid Empire (modern-day Iran), driven by a combination of economic opportunity and religious persecution. Their arrival coincided with Dhaka’s rise as a major commercial hub of the Mughal Empire, particularly after it became the provincial capital of Bengal in 1608.

Masters of Long-Distance Trade

Armenian traders quickly established themselves as key intermediaries between South Asia, Persia, Southeast Asia, and Europe. They developed an extensive commercial network that allowed them to dominate several lucrative trades, including:

- Dhaka muslin and fine textiles

- Silk and cotton goods

- Saltpeter, an essential ingredient for gunpowder

- Betel nut and spices

By the mid-18th century, Armenian merchants had become some of the most powerful exporters in Bengal. Historical records indicate that by 1747, Armenians were exporting more Dhaka cloth than the British, Dutch, and French trading companies combined—an extraordinary achievement for a small, non-imperial community.

Settlement Patterns

Early Armenian settlers initially lived in areas such as Moulvibazar and Nolgola, close to Dhaka’s riverine trade routes. Over time, they consolidated their presence in a neighborhood that later became known as Armanitola, literally meaning “the place of Armenians.” This area emerged as the social and commercial heart of the community.

The Golden Age: 19th Century Influence

The 19th century marked the height of Armenian influence in Dhaka. As Mughal power declined and British colonial rule expanded, Armenian merchants adapted swiftly, transitioning from international traders into landlords, financiers, and civic leaders.

Pioneers of the Jute Trade

One of the most significant Armenian contributions to Bengal’s economy was their role in the early jute trade. In the second half of the 19th century, Armenians were among the first to recognize jute’s global commercial potential.

Prominent Armenian firms such as:

- Messrs Sarkies & Sons

- Messrs David & Co.

came to dominate the industry. The latter was owned by Marcar David, often referred to in colonial accounts as the “Merchant Prince of East Bengal.” These enterprises laid the groundwork for what would later become one of the region’s most important export industries.

Transforming Urban Life

Armenians also played a visible role in reshaping everyday life in Dhaka:

- They introduced the ticca-garry, a horse-drawn carriage that became the city’s primary mode of transport until the early 20th century.

- Many Armenian families acquired zamindari estates, increasing their political and social influence.

- They participated actively in civic affairs, often acting as intermediaries between local elites and colonial authorities.

Education and Philanthropy

One of the most enduring Armenian contributions to Dhaka’s social fabric is Pogose School, founded in 1848 by Nicholas Pogose, a wealthy Armenian merchant. It was the first private school in Dhaka and continues to operate today, making it one of the oldest educational institutions in the city.

Landmarks and Architectural Legacy

While the Armenian population has disappeared, their physical and cultural footprint remains deeply embedded in Old Dhaka.

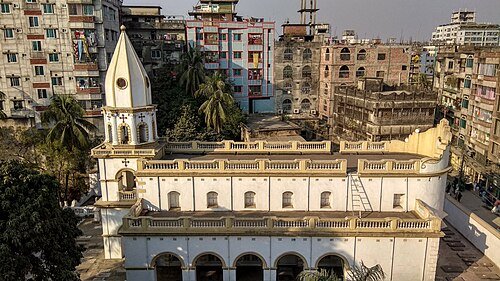

Armenian Church of the Holy Resurrection

Built in 1781 on the site of an earlier chapel, the Armenian Church of the Holy Resurrection stands as the most powerful symbol of the community’s legacy. Located in Armanitola, the church complex contains approximately 400 graves, offering a rare historical archive in stone.

- The oldest tombstone, belonging to a merchant named Avietes, dates back to 1714

- Many epitaphs are inscribed in Armenian, Persian, and English, reflecting the community’s cosmopolitan identity

The church was not only a place of worship but also the social and administrative center of Armenian life in Dhaka.

Bangabhaban and Ruplal House

Several of Dhaka’s most significant historical buildings are linked to Armenian ownership:

- Bangabhaban, the official residence of the President of Bangladesh, was originally a Bagan Bari (garden house) owned by an Armenian merchant named Manuk, before being sold to the Nawab of Dhaka.

- Ruplal House, one of the grandest 19th-century mansions along the Buriganga River, was originally built by the Armenian zamindar Aratoon, before later being purchased by the Ruplal brothers.

Decline of the Community

The Armenian presence in Dhaka began to decline in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Several factors contributed to this gradual disappearance:

- British companies increasingly monopolized the jute trade

- Economic power shifted toward Kolkata, the colonial capital

- Younger generations migrated to India, Europe, and Australia

By the time of Partition in 1947, the Armenian population in Dhaka had already dwindled to a handful of families.

The Last Armenian of Dhaka

For decades, the community was represented by a single figure: Michael Joseph Martin (also known as Mikel Housep Martirossian). He served as the sole caretaker and informal representative of the Armenian Church until his death in 2020.

With his passing, an unbroken human link to Dhaka’s Armenian past came to an end.

Legacy and Memory

Today, there are no permanent Armenian residents in Dhaka. However, the Armenian Church remains maintained under the Armenian Church of Bangladesh and occasionally hosts visiting priests. Armanitola’s name, historic schools, and architectural landmarks continue to silently testify to a community that once stood at the center of Dhaka’s commercial life.

The Armenians of Dhaka exemplify how a small diaspora, through trade, education, and civic engagement, helped shape a city’s destiny. Their story is an essential chapter in understanding Old Dhaka, not as an isolated city, but as a crossroads of global commerce and culture.