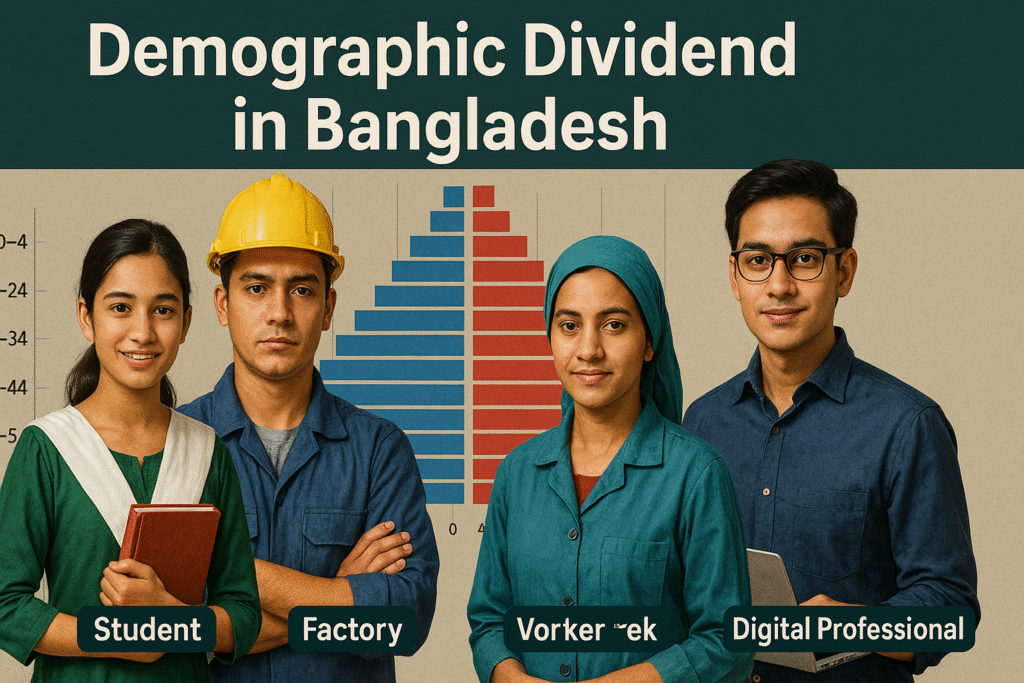

The demographic dividend in Bangladesh is one of the most important opportunities in the country’s modern history. This dividend, often called the demographic window of opportunity, occurs when the share of the working-age population becomes larger than the dependent population of children and the elderly.

Bangladesh has reached this stage. According to the United Nations Population Fund, nearly two-thirds of the nation’s people are now between the ages of 15 and 64. The 2022 census data shows that 65.7 percent of Bangladesh’s population is in this working-age group. That is more than 114 million people out of a population of 175 million. This share is expected to remain significant until the late 2030s.

The World Bank highlights that the age dependency ratio has steadily declined, meaning fewer dependents are supported by each worker. At the same time, the fertility rate has dropped from more than six children per woman in the 1970s to around 2.0 in 2024. These statistics confirm that Bangladesh has entered a demographic window. The challenge now is how to use it.

Understanding the Demographic Dividend in Bangladesh

The demographic dividend in Bangladesh is not just about population numbers. It is about potential. When a country has more people of working age, it has a chance to accelerate economic growth. More workers mean higher production, more savings, and stronger investment. However, the dividend is not automatic. Without policies to create jobs, improve skills, and strengthen health systems, the opportunity can be wasted.

Bangladesh’s working-age population grew sharply in the last four decades. In 1980, only 52 percent of the population was aged 15–64. By 2000, the figure reached 60 percent. Today it is above 65 percent. This transformation is a direct result of lower fertility, improved health services, and rising life expectancy, which now stands at nearly 73 years.

Why the Demographic Dividend Matters

The demographic dividend in Bangladesh is critical for several reasons. First, it comes at a time when the nation is aspiring to become an upper-middle-income country by 2031. Second, it coincides with a period of rapid urbanization. Already more than 38 percent of Bangladeshis live in cities, and this is projected to cross 50 percent by 2040. A larger urban workforce means opportunities in industry, services, and technology.

Third, the dividend period is temporary. Analysts predict that Bangladesh’s working-age share will peak in the next decade and then decline. The proportion of elderly people is already rising, with about 7 percent of the population above 65 years in 2025. By 2050, this could be more than 20 percent. Without preparation, the window may close before the country fully benefits.

Youth as the Core of the Demographic Dividend

At the heart of the demographic dividend in Bangladesh are its young people. More than 75 percent of the population is under the age of 41, according to The Business Standard. The median age is about 26 years. This means the majority of Bangladeshis are in their most productive years.

This youth bulge creates opportunities for innovation, entrepreneurship, and labor supply. But it also brings risks. If jobs are not created at the pace of demand, millions of young people may face unemployment or underemployment. Currently, youth unemployment hovers around 11 percent, higher than the national average.

Economic Potential of the Dividend

The potential gains from the demographic dividend in Bangladesh are significant. Economists estimate that countries experiencing demographic dividends can see GDP growth rates increase by 2 percent or more per year, provided they adopt the right policies.

Bangladesh has already demonstrated strong growth, averaging over 6 percent annually for two decades before the pandemic. The garment industry, remittances, and services have fueled this progress. If the growing workforce can be absorbed into productive sectors like technology, manufacturing, and renewable energy, Bangladesh could sustain rapid growth.

Barriers to Reaping the Dividend

Despite the promise, challenges remain. Education quality is uneven. While primary enrollment is nearly universal, only about 25 percent of students finish higher secondary school. Skill gaps limit youth participation in high-value industries. According to UNDP, only 19 percent of the workforce is engaged in formal employment. The rest are in informal jobs with low security and productivity.

Health also affects productivity. Malnutrition remains a concern, with around 28 percent of children under five suffering from stunting. Poor health in childhood reduces capacity in adulthood. In addition, gender inequality restricts women’s economic participation. Female labor force participation is about 38 percent, compared to over 80 percent for men. Closing this gap could significantly boost the economy.

The Role of Migration and Remittances

An important factor in the demographic dividend in Bangladesh is migration. Millions of Bangladeshis work abroad, mainly in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. In 2022, remittances amounted to $21 billion, providing a crucial source of income.

However, reliance on low-skilled migration limits long-term gains. Expanding training for higher-skilled jobs abroad could increase remittance earnings. At the same time, creating attractive opportunities at home would reduce brain drain and keep talent in the country.

Lessons from Other Countries

Other Asian nations provide lessons. South Korea and Singapore turned their demographic dividends into engines of growth by investing in education, technology, and governance. India is currently experiencing its own demographic dividend, while Japan shows what happens when populations age without strong preparation.

For Bangladesh, the lesson is clear. The demographic dividend in Bangladesh can become a burden if reforms are delayed. But with the right strategy, it can become the nation’s greatest strength.

Strategies to Harness the Demographic Dividend

Bangladesh must act on several fronts. First, education must improve in quality, not just quantity. Skills training, vocational education, and digital literacy are vital. Second, the economy must diversify beyond garments. Sectors like IT, renewable energy, agro-processing, and logistics can absorb more workers.

Third, healthcare investments are critical. Healthy workers are productive workers. Fourth, empowering women is non-negotiable. Closing the gender gap could add billions to GDP. Finally, governance and infrastructure must support sustainable growth. Roads, ports, energy, and digital networks must keep pace with population demands.

Risks of Missing the Window

If the demographic dividend in Bangladesh is not managed well, risks will rise. Youth unemployment could increase frustration, leading to social unrest. Informal jobs could trap workers in low productivity cycles. An aging population could arrive before economic growth strengthens. This would strain pensions, healthcare, and social services.

The 2023 decline in working-age share from 66.6 percent in 2021 to 65.1 percent shows that the window may already be narrowing. This signals urgency. Time is not unlimited.

Global Importance of Bangladesh’s Dividend

The demographic dividend in Bangladesh matters beyond its borders. With nearly 175 million people, Bangladesh is the eighth-most populous country in the world. How it manages its youth population will influence regional stability, migration flows, and global supply chains.

International partners have an interest in supporting Bangladesh’s success. From climate change adaptation to labor mobility agreements, global cooperation can help maximize the benefits of this window.

The demographic dividend in Bangladesh represents a rare opportunity. With two-thirds of the population in working ages and fertility rates at replacement level, the country is poised for growth. But this dividend will not last forever. The window may close within two decades as the population ages.

Bangladesh must invest in education, healthcare, gender equality, and job creation. If it does, it can turn its youth bulge into a source of economic power. If it does not, the dividend may turn into a burden.

The choice is urgent, but the potential rewards are immense. Bangladesh’s future depends on how it uses this moment.