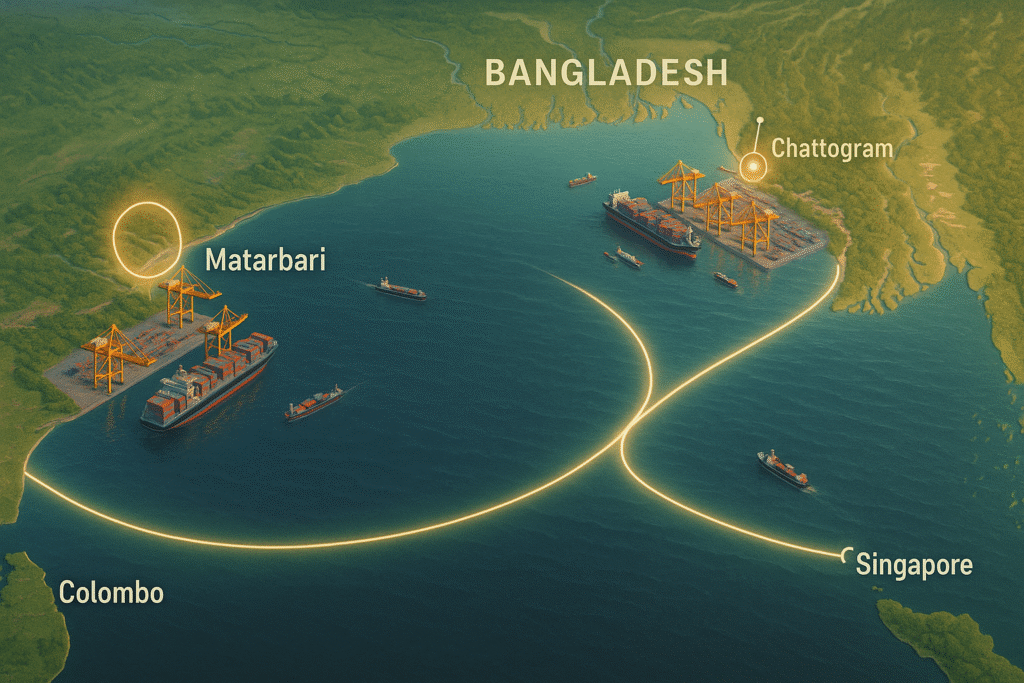

Bangladesh stands at a strategic maritime crossroads, its coastline opening onto the Bay of Bengal where major East-West shipping routes and emerging regional logistics corridors intersect. Two flagship infrastructure projects, the Matarbari Deep Seaport and the Bay Terminal at Cox’s Bazar and Chattogram, have the potential to reshape how cargo moves through the northern Indian Ocean, and to reposition the country as a Transshipment Hub.

This analysis draws on project facts and regional port benchmarks to explain how those projects could deliver scale, speed, and competitive economics, what obstacles could limit gains, and how Bangladesh compares with established transshipment centers such as Colombo, Singapore, and Malaysia, as well as with new competitors in the region.

Natural draft at Matarbari enabling larger vessels to operate

Matarbari’s biggest technical advantage is water depth, the natural seabed in the area offers a deep draft that allows larger mother vessels to berth directly. Publications and project briefs indicate a natural depth in the Matarbari area of roughly 18 to 18.5 metres, enabling berthing of vessels in the 8,000 TEU class or more, and reducing the need for smaller feeder transhipments.

This depth, combined with a planned engineered access channel, gives Matarbari immediate scale benefits, because larger ships can call without draft restrictions that constrain Chattogram’s inner harbour. The ability to handle larger vessels is a precondition for any port aspiring to be a Transshipment Hub, because liner operators prioritise ports that can accept mother ships without costly transshipment at sea.

Bay Terminal’s berth length and modern infrastructure to lower vessel turnaround time

The Bay Terminal project is explicitly designed to expand Chattogram Port’s capacity, by delivering long berth lengths, climate-resilient breakwaters, and modern access channels that can accommodate simultaneous docking of multiple large vessels. Project documents and donor summaries indicate that the Bay Terminal will include several kilometres of berth frontage, enabling four to five large vessels to dock concurrently, and thereby reducing congestion, queueing and idle time. Faster ship turnaround and fewer tidal and draft constraints are central to the economics of transshipment operations, they attract shipping lines when a terminal can guarantee predictable berthing windows and fast container handling. The World Bank financing package of roughly $650 million for the Bay Terminal Marine Infrastructure Development Project underscores the project’s intended scale and its role in improving port access and efficiency.

Complementary roles: Matarbari for deep-draft mother vessels, Bay Terminal for hub operations, feeder links

A realistic strategy for Bangladesh is not to aim to replicate any single existing hub, but to combine strengths. Matarbari’s deep-draft berths can host large mother vessels on major East–West strings, while the Bay Terminal can act as an efficient handling and redistribution node, with multiple berths and improved hinterland links for feeder services.

Together, these nodes create an integrated port system: Matarbari reduces the need for transshipment outside national waters, and Bay Terminal provides the capacity and redundancy to handle high-frequency feeder operations that distribute cargo to regional destinations. This complementary model is what can transform port geography into a true Transshipment Hub proposition.

Hinterland connectivity is the Achilles heel, road and rail must scale with berth capacity

A port cannot be a true Transshipment Hub if its supporting logistics fail to match quay capacity. That means robust, high-capacity road and rail links, efficient inland container depots, and fast customs and intermodal procedures. Bangladesh has committed to road and rail links from Matarbari, including long access roads and proposed double-line rail connections, yet these links require time and sustained investment to be operational at the scale the ports will demand. Until hinterland connectivity and intermodal terminals are in place, some of the benefits of deeper berths and longer quays will remain unrealized, because containers will face inland bottlenecks and dwell time will rise.

Demand and regional trade patterns that favor a new hub, particularly for South and Southeast Asia trades

Several structural trends point to opportunity. Regional trade volumes have grown, and the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and East Africa trades increasingly use feeder-and-mother vessel networks. Established transshipment centres like Colombo and Singapore have shown the market is willing to concentrate transshipment flows at efficient nodes. For example, the Port of Colombo handled nearly 7.8 million TEUs in 2024, showcasing how a single efficient hub can process vast transshipment flows, and Singapore processed over 40 million TEUs in 2024, driven largely by transshipment traffic. Bangladesh can tap north-south and east-west flows if it offers faster, cheaper, and more reliable handling than proximate alternatives.

Fierce regional competition, existing hubs and new entrants will respond

Gaining share in transshipment markets means displacing volumes from entrenched hubs, or convincing new services to reroute. Colombo, Singapore, and Port Klang already act as primary hubs for regional lines, benefiting from deep networks, liner concentration, and logistic ecosystems.

Moreover, India’s recent investments, such as the operationalisation of Vizhinjam in Kerala and the development of other deep-draft ports, represent direct competition. Vizhinjam has rapidly scaled operations and impressed with deep-draft handling, which demonstrates how quickly market share can be contested when new capacity is available. Bangladesh will compete not only on technical parameters, but on operational consistency, political risk perception, customs efficiency, and the attractiveness of shipping line commercial deals.

Cost competitiveness, faster turnaround and lower feeder miles can lower liveliness cost for shippers

Transshipment economics are driven by total supply chain cost, not only berth fees. Matarbari and Bay Terminal can lower carrier and shipper costs by reducing feeder distances, cutting fuel use, and shortening transit times between mother vessel and final destinations in Northeast India, Myanmar, and northern Bay states.

If Bangladesh’s terminals can consistently offer lower terminal handling charges, reduced waiting time, and efficient inland moves, the combined cost advantage can attract liners, especially on services that aim to shorten port rotation times and optimize container flows.

Institutional and regulatory reforms must match infrastructure investment, customs and tariff regimes matter

A common lesson from port development worldwide is that physical infrastructure is necessary, but insufficient. Port governance, tariff transparency, predictable labour relations, and modern customs procedures are equally vital. Shipping lines evaluate the full operational environment, including dwell times, paperwork, and corruption risk.

The Bay Terminal project includes modernization elements, and donor involvement indicates reform expectations, yet implementation will be decisive. Without streamlined customs, one-stop inspections, bonded logistics zones, and electronic documentation that match the best regional practices, Bangladesh’s Transshipment Hub ambitions will face persistent frictions.

Environment and climate resilience, design that acknowledges sea-level and extreme weather risk

Both projects are being framed with climate resilience in mind, the Bay Terminal documentation explicitly references a climate-resilient breakwater and engineering to withstand seasonal extremes. A resilient port is more attractive to global liners, because service reliability underpins scheduling commitments. Integrating resilience reduces long-term costs and underwrites the business case for promoting these nodes as a stable Transshipment Hub for liner schedules that are sensitive to weather-related disruption.

Financing, cost overruns and geopolitical complexity could slow timelines

Large port projects face financing and execution risk. Matarbari’s development has seen multilateral and bilateral involvement, likewise the Bay Terminal secured significant World Bank financing. Still, timelines often slip, and cost overruns can change commercial calculations. Moreover, geopolitical sensitivities with major partners require careful diplomacy, because ports are strategic infrastructure assets. Managing these political and financial dynamics while preserving transparent procurement and operator confidence is crucial.

Comparison with Colombo, Singapore and Malaysia: Evidence-based lessons

Colombo and Singapore are market leaders because they combine deep natural drafts, scale, liner concentration, modern terminals, and a complete logistic ecosystem. Singapore processed over 40 million TEUs in 2024 and remains the world’s largest transshipment hub, its business model is built on unmatched connectivity and value-added logistics. Colombo reached nearly 7.8 million TEUs in 2024, leveraging its location and aggressive transshipment marketing. Malaysia’s Port Klang and other terminals cluster significant volumes, ranking in the millions of TEUs. These hubs benefit from decades of liner alliances routing and from downstream logistics services that keep containers moving quickly. To compete, Bangladesh must match not only depth and berth length, but also digital workflow, steep productivity at quay, and commercial incentives that persuade carriers to add calls or re-route transshipment strings.

Comparison with India and other neighboring countries, where new deep ports are changing the game

India has accelerated port investments, with Vizhinjam demonstrating how quickly a deep-draft, well-marketed facility can attract significant volumes. Vizhinjam’s early throughput and capacity to handle ultra large container vessels show that new greenfield projects can rapidly alter regional cargo flows.

For Bangladesh, this means a narrow window of opportunity, and a need to offer distinct commercial advantages. Bangladesh can leverage proximity to major producing clusters in Northeast India and to fast-growing import markets, if its terminals can promise shorter total door-to-door times. Partnerships with liner operators, competitive transshipment tariffs, and reliable scheduling will determine whether Bangladesh wins diverted volumes or remains a hinterland reliant on other hubs.

Practical steps to accelerate the transformation into a transshipment hub

First, operationalize digital port community systems that reduce paperwork and dwell times. Second, finish hinterland road and rail links concurrently with quay completion, so increased quay capacity is not stranded. Third, introduce tariff incentives and time-limited introductory rates to entice a set of anchor liner services, this will create visible schedules that attract feeders. Fourth, pursue targeted free-trade or bonded logistics zones near terminals to capture value-added logistics and encourage cargo consolidation in-country. Fifth, prioritise stable governance and transparent labor relations, these reduce risk premia that carrier’s price into routing decisions.

Realistic optimism and a long runway

Matarbari and the Bay Terminal form a credible foundation for a new Transshipment Hub in the Bay of Bengal, they provide the technical prerequisites of depth, berth length, and modern access channels, and the World Bank and other partners have signalled the international financial and institutional backing required for success. However, the transformation will not be automatic, because ports are ecosystems in which hardware, software, and hinterland networks must evolve in parallel.

If Bangladesh executes on connectivity, governance, and commercial incentives while maintaining high operational productivity, it can capture a meaningful share of regional transshipment flows and relieve congestion in neighboring nodes. The prize is substantial, the competition is intense, and the timeline requires steady, coordinated policy action.